202207202332

Status: #idea

Tags: HBP

Hepatic resection

Liver surgery, encompassing advanced and complex procedures[17,26], falls into the category of intermediate or high-risk surgical operations, with mortality/major cardiovascular event rates ranging from 1%–3% to ≥ 5%

Compared to the traditional open approach, minimally invasive liver resections are associated with reduced blood loss, less postoperative pain, much rare ascitic decompensation, lower incisional hernia rates, faster postoperative recovery, and shorter hospital stays

In major liver resections, ensuring a sufficient future liver remnant (FLR) is crucial

Pre-operative liver volumetry, calculated via computerized tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is mandatory to prevent fatal PHLF. The parenchymal function can be dynamically assessed using indocyanine green (ICG) clearance

A successful strategy to increase FLR volume involves portal and hepatic vein embolization of the liver portion to be resected, usually performed by interventional radiologists

ALPPS (Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein ligation for Staged Hepatectomy) - has been proposed[19,20]. This two-stage technique increases the treatment options for otherwise unresectable tumors. In the first stage, the portal branch ipsilateral to the hemiliver to be removed is ligated. Any lesions in the hemiliver to be preserved are resected, and a parenchymal transection along the Cantlie line is performed. Hypertrophy of the lobe to be preserved is usually achieved within about two weeks. The second stage, usually 15 to 20 days later, is undertaken following a CT scan volumetry and is performed when appropriate hypertrophization of the FLR is confirmed. In this second stage, the hemiliver is removed by transecting the artery, the biliary duct, and the hepatic vein.

Although ALPPS is effective in inducing hypertrophy of the remnant liver, it is associated with high surgical complications and mortality rates

Anatomic resection is defined as the resection of one or more hepatic segments, sectioning the segmental Glissonian arterial and portal pedicle, and resecting all the dependent parenchyma

Anatomic resections are associated with shorter surgical times and reduced blood loss compared to non-anatomical resections

In non-anatomical “wedge” resections, the main goal is to preserve liver parenchyma

Hepatic resections are classified as minor (involving up to two segments) or major (involving more than two segments)

Important surgical manouevres

- surgical manipulation of liver

- for best exposure of anatomical structure

- acutely ↓ VR from IVC

- severe abrupt arterial hypertension

- selective or total vascular clamping before resection

Among the surgical maneuvers and manipulations anesthesiologists must be familiar with due to their potential relevant hemodynamic impact are: (1) The surgical “manipulation” of the liver, aiming at the best exposure of the anatomical structures and able to acutely reduce the venous return from the IVC, leading to severe, abrupt arterial hypotension; and (2) selective or total vascular clamping before resection, aimed at reducing bleeding

Surgical haemostatic solutions

- Intraoperative ultrasound (US),

- CUSA Dissector (Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator)

- Ligasure

- Argon beam coagulation

- topical hemostatic agents

- tissue adhesive & fibrin sealants

Methods used to assess residual function after liver resection include: (1) Volumetric assessment (% future liver remnant volume,), with a remnant volume being sufficient if at least 20%–30% of the native volume (or 40% in cases of chemotherapy); and (2) functional assessment, primarily based on IGC clearance, with preoperative R15 (retention rate at 15 minutes) values above 15%-20% indicating a relative surgical contraindication

A major limitation in using ICG clearance could be serum bilirubin levels > 6 mg/dL, able to introduce a significant bias to the accuracy of the R15 value, leading to an overestimation of the liver function deterioration

The presence of cirrhosis, if properly assessed, is no longer an absolute CI due to advancements in surgical techniques

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, recently redefined, is increasingly diagnosed in liver surgery candidates and warrants particular attention, particularly in cases of moderate-to-severe diastolic dysfunction

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

HPS is characterized by varying degrees of hypoxia (mild: PaO2 < 80 mmHg; moderate: PaO2 60-80 mmHg; severe: PaO2 50-60 mmHg; extremely severe: PaO2 < 50 mmHg). It is associated with an increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (> 15 mmHg in room air) due to intrapulmonary vascular dilatation (shunt). Symptoms include dyspnea at rest or upon exertion, with platypnea (dyspnea and desaturation in orthostatic position) and orthodeoxia (reduction of PaO2 from supine to orthostatic position) present in 25%-30% of cases. Screening and further investigation are required for SaO2 < 96% in room air

While there is no definitive treatment, Methylene Blue may be considered for refractory hypoxia (anecdotal reports)

Portopulmonary hypertension

PoPH, associated with portal hypertension, is present in 2%-5% of CLD patients and involves anatomic changes in the pulmonary vascular bed and increased circulating pulmonary vasoconstricting agents (e.g., endothelin-1)[58,63,75]. Diagnosis is based on the presence of mean pulmonary pressure (mPAP) > 25 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance > 240 dyne/s/cm-5 with central venous pressure (CVP) < 5 mmHg and pulmonary wedge pressure < 15 mmHg

PoPH is classified as mild (mPAP 25-35 mmHg), moderate (mPAP 35-45 mmHg), or severe (mPAP > 45 mmHg)

In cases where transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) estimates systolic pulmonary pressure > 45 to 50 mmHg, consultation with a cardiologist and further investigation with right heart catheterization are mandatory

Among the available treatment options are phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, prostaglandins, endothelin-1 receptor antagonists, and nitric oxide for the perioperative period

Hepatorenal syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS, now HRS - AKI), is characterized by intense renal vasoconstriction, requires careful evaluation with hepatologists, and involves treatment with terlipressin and albumin

Before the development of new AKI criteria, HRS was divided into two types, with different prognoses, type 1 having the worst outcome

Serum creatinine may present interpretative concerns in sarcopenic patients and/or in the hyperbilirubinemic cirrhotic patient, limitations to be considered when assessing preoperative renal function. Often, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is discrepant with serum creatinine (elevated BUN vs “normal” creatinine), and might provide a more accurate description of renal dysfunction

The best approach to protect renal function during the perioperative period includes maintaining mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg, to ensure renal perfusion pressure - and tailoring fluid balance and use of pressors implementing appropriate invasive hemodynamic monitoring (invasive arterial pressure and minimally invasive cardiac output if indicated)

The use of mannitol and dopamine, although still considered, lacks evidence

The hemostatic profile of a non-cirrhotic patient undergoing liver surgery is expected to be normal. In cirrhotic patients, however, the profile is not “naturally” anticoagulated , but instead “rebalanced,” with coexisting procoagulant (increased factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, reduced ADAMTS-13, reduced natural anticoagulants like Antithrombin, Protein C, Protein S) and anticoagulant features (reduced synthesis of coagulation factors, hypopiastrinemia, impaired platelet function, hypofibrinogenemia)

The coagulation profile is often activated (increased d-dimer), with the risk of consumption coagulopathy. Increased fibrinolysis and endogenous heparin-like products may also be observed

Prolonged PT/INR and aPTT/R do not necessarily imply an increased hemorrhagic risk, but rather an “instability” of the hemostatic balance, which can shift towards a prothrombotic or prohemorrhagic state depending on the type of insult

Intra-op

key objectives of intraoperative anesthesia management include

- maintaining adequate anesthesia depth and analgesia

- core temperature control,

- cardiometabolic stability

- stable circulatory, respiratory, and metabolic profiles

- appropriate fluid balance

- minimize blood loss

Evidence suggests that ischaemic preconditioning and even “postconditioning” (adaptation to ischemic injury and remodulation of ischemia-reperfusion syndrome) can be facilitated by volatile anaesthetics like sevoflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane

haemodynamics

common causes of hemodynamic instability include

- blood loss during isolation / dissection / resection,

- liver mobilization manouevres (“dislocation”)

- compressions / distortions of the IVC

- → ↓VR

- gas embolization

- rare

- can occur if ↓↓CVP / extreme hypovolemia during exposure of large venous vessels

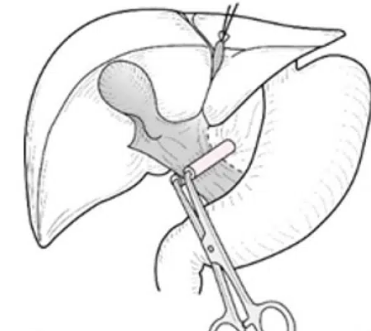

Pringle manouevre

- occlusion of hepatic vascular pedicle

- = portal triad

- inflow occlusion

- to ↓ blood loss

- effects on morbidity / mortality unproven

- a/w acute liver injury / delay regenerative activity

- Duration:

- continuoues: 15-30min

- intermittent

- clamp 10-15min → declamp 5-10min

- hepatectomy interrupted during declamp

- akin to preconditioning

- ↓duration by 50% in cirrhotic livers

Haemodynamics:

- ↓VR & CO ~15%

- usually well tolerated ∵ ↑ orthosympathetic tone

- hypotension uncommon

- usually modest ↑SBP

- ∵ ↑SVR

Selective vascular occlusion

clamping inflow of resected hemiliver

Total clamping

- occlusion of infrahepatic & suprahaptic IVC

- ↓↓BP 40-50%

- ↓↓VR & CO up to 50%

- compensatory tachycardia

- Duration up to 100min

- very rarely needs aortic clamping

In liver surgery, minimally invasive monitoring of CO, left heart function, and dynamic parameters can largely address the controversy around maintaining low CVP (< 5 mmHg) during liver dissection, a standard technique to reduce blood loss, debated if used without an appropriate rationale

↓ CVP

CVP monitoring aiming at low values (< 5 mmHg), is now questioned. CVP values can be reduced implementing different strategies (increased diuresis, restrictive fluid management, anti-Trendelenburg position, use of vasodilators, post-induction phlebotomy) but able to induce side effects

Values of SVV or PPV > 13% (normal < 9%, with a grey zone between 9 and 13%) are more reliable than the absolute value of CVP in maintaining a relative hypovolemic state while keeping CO within normal limits

Fluid

In modern anesthesia practice during major abdominal surgery, including liver resection, the restrictive fluid therapy is championed as a mainstay of anesthetic management: At the end of surgery, the best outcomes are associated with even or only slightly positive balance

Analgesia

Open resective surgery historically involves significant postoperative pain. Thoracic epidural blocks (TEB) have become popular, reducing respiratory complications and systemic sympathetic response when appropriately used

widespread adoption of TEB has been limited by concerns about perioperative hemodynamic instability and risk of spinal hematoma (secondary to possible postoperative hemostatic alterations): recent ERAS guidelines no longer recommend TEB due to the evidence of effective alternatives

there is growing interest in alternative techniques such as continuous local infiltration with wound catheters, “single shot” subarachnoid analgesia with local anesthetics and intrathecal opioids, and patient-controlled analgesia

Posthepatectomy liver failure

most feared Cx w/i first 30 postop days

mortality 30-40%

Risk factors

- patient factors

- pre-op comorbidities

- pre-existing liver disease

- liver functional reserve

- surgical factors

- extent of resection

- long Pringle Manouevre

Pathophysiology

'physiological' regeneration of liver after hepatectomy triggered by ↑PV ∵ ↑ portal inflow

(rapid regeneration occurs w/i 2-4 wks in normal liver even w/ resection up to 75% of native liver mass)

- ↓ liver volume → ↑vascular shear stress & ↑ intrahepatic vascular resistance

- overwhelming ↑ in portal pressure : 'small-for-flow' syndrome

- excessive shear stress → inflammatory response

- release of nitric oxide & cytokines

- inhibit liver regeneration

- parenchymal necrosis

- hepatocyte apoptosis

- microvascular thrombosis + endothelial dysfunction → impaired hepatic microcirculation

- surgical trauma + ischaemia-reperfusion injury → inflammatory storm

- intra-op factors favouring ischaemia-reperfusion injury

- hepatic venous congestion

- fluid overload

- right ventricular dysfunction

- ↑ airway pressure

- arterial hypotension

- ↑ blood loss

- prolonged periods of vascular occlusion

- hepatic venous congestion

- intra-op factors favouring ischaemia-reperfusion injury

50-50 criteria on POD5 by Belghiti (2005)

- bili >50umol/L

- PT <50%

- validated in 2009

- predict mortality

The International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS, 2011)[147] provides the reference standard for PHLF, using three degrees of severity (A, B, C) based on INR prolongation, bilirubin increase, elevated lactate, and hepatic encephalopathy levels. Level C PHLF, requiring artificial support of organ failures, mandates ICU observation, level B being considered for HDU observation; mortality rate (absent in group A) is 12% for level B, reaching 54% for level C

The onset of PHLF can vary, typically occurring days to weeks post-surgery, with normalization expected within 1 to 3 weeks

PHLF treatment

- treat 'remediable' causes e.g.

- obstructive jaundice

- vascular obstruction

- infection / sepsis

- perihepatic collection / abscess

- general supportive measures:

- haemodynamics

- crystalloid / albumin for hypovolaemia

- noradrenaline / terlipressin for vasodilation

- if advanced hepatic encephalopathy:

- early intubation + protective ventilation

- early CRRT

- TEG to ↓ overuse of FFP

- haemodynamics

- interventions

- if excessive portal flow:

- splenic artery embolisation

- octreotide

- beta blocker

- ↓ PV pressure

- N-acetylcysteine controversial

- if excessive portal flow:

- extracorporeal treatment

- inadequate evidence for routine use

- if used : serve as bridge to liver transplantation

- liver transplantation

References

Perioperative Management for Hepatic Resection Surgery

Major Liver Surgery and the Anesthesiologist Towards a Proactive Strategy